When the Civil War broke out, the government of the United States was in a dilemma as to how to provide a sufficient quantity of shoes for the armies of the North. So many shoemakers had volunteered that many of the small shoe shops, where most of the shoes were made, were now without shoemakers to make the shoes or even finish the ones in process. In Marblehead, manufacturers rode around town , waving rolls of bills, and offering double and triple wages to shoemakers who would finish their work before leaving for the war. The price of shoes more than doubled as the shortage became critical.

Congress considered the removal of the tariff on shoes, so that army shoes, as well as civilian shoes, could be imported from England. A crisis was at hand in American shoemaking. The armies of both the North and South were shod with footwear, where the outsole was attached by wooden pegs, which failed from the harsh wet Winter weather. Many went barefoot or with bandages wrapped around their feet.

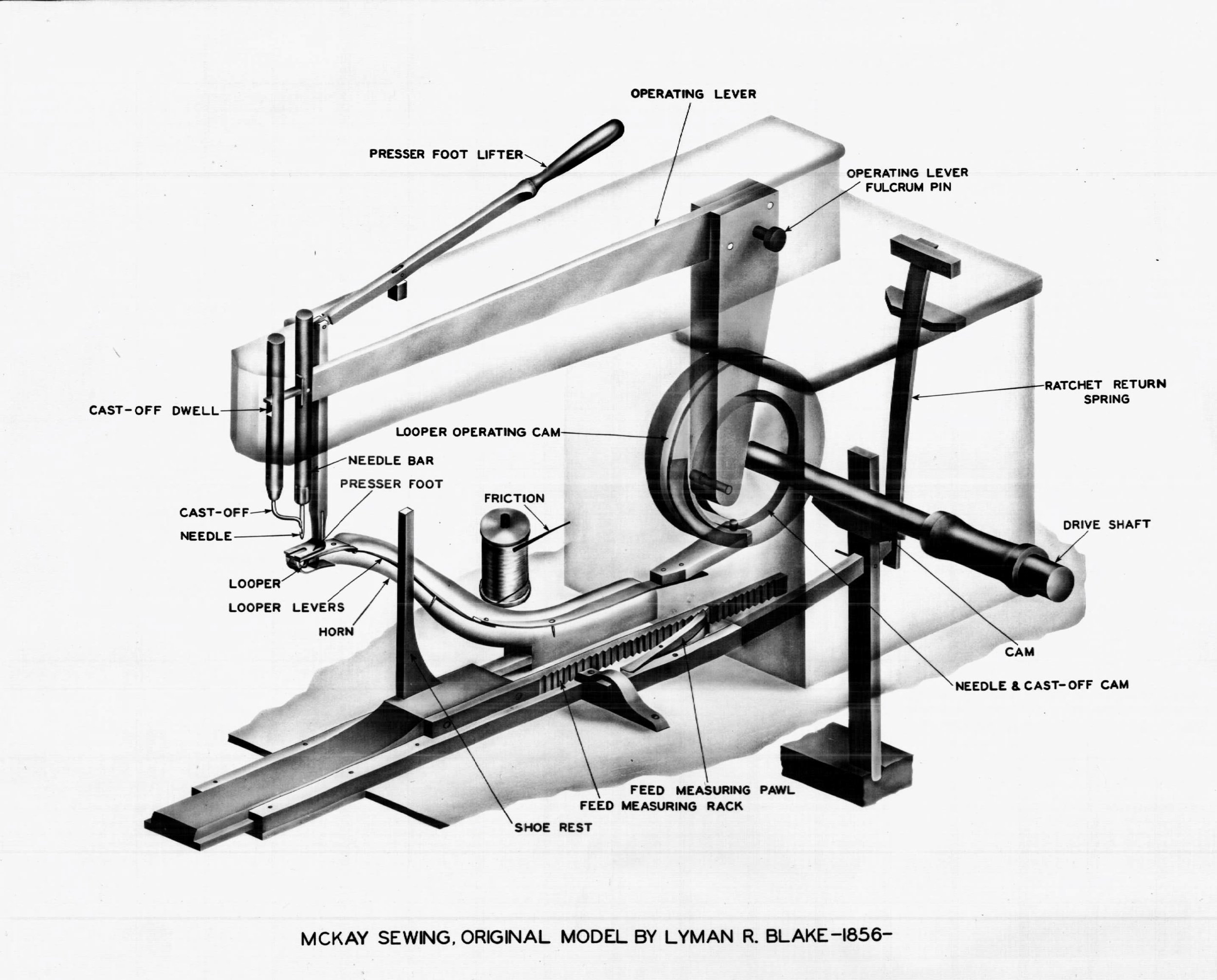

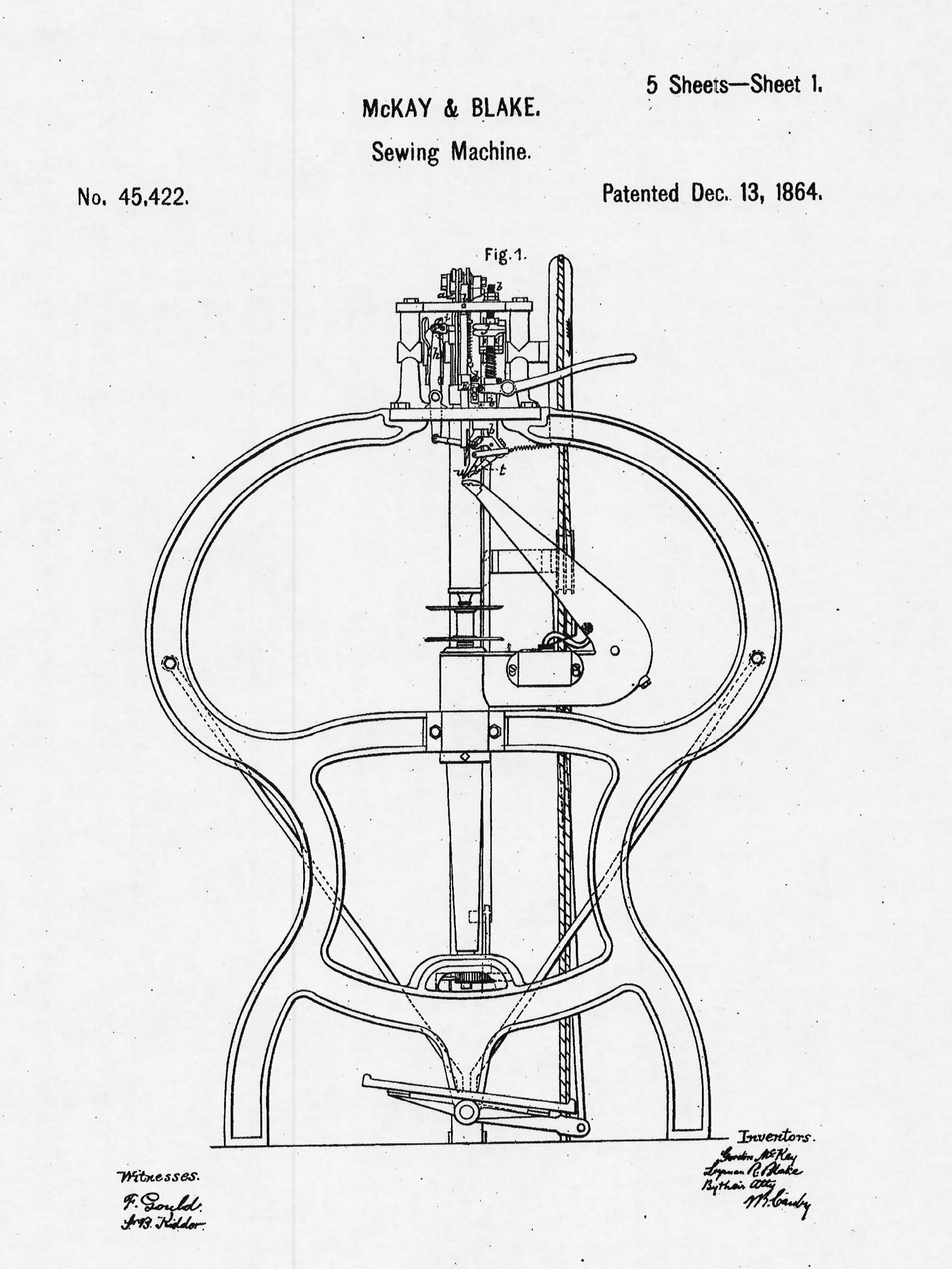

It was about this time that Colonel Gordon McKay introduced a specialized sewing machine for sewing the soles of the shoe to the upper or top portion. The productivity of this machine replaced the shoemakers who had left for the front. This was also the beginning of the factory system of making shoes. The quality of the the shoes produced on the McKay machine was superior to the pegged construction. The price of shoes declined at a very substantial rate, providing consumers with lower cost footwear and much better quality.

This machine was invented by Lyman R. Blake, a shoemaker and Singer Sewing Machine Co. technician. Blake was born in South Abington, MA (now Whitman, MA) on August 24, 1835. His initial exposure to shoemaking was in his brother Samuel’s factory, working his way up to foreman of the upper fitting department. After returning to school for six months he went to work in the Gurney and Mears shoe factory and in 1857 became a partner in the shoe firm, but unfortunately the firm failed after two years.

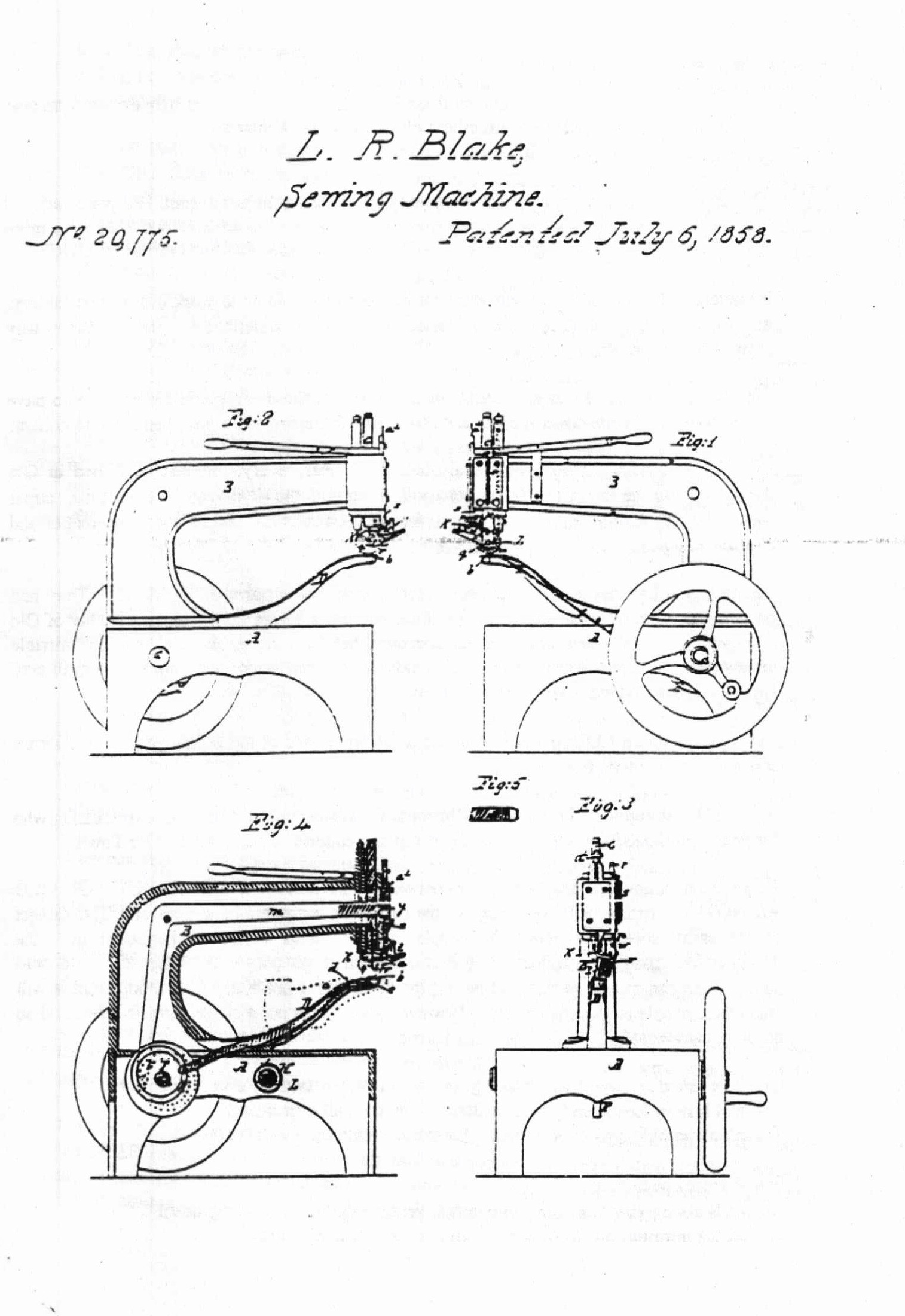

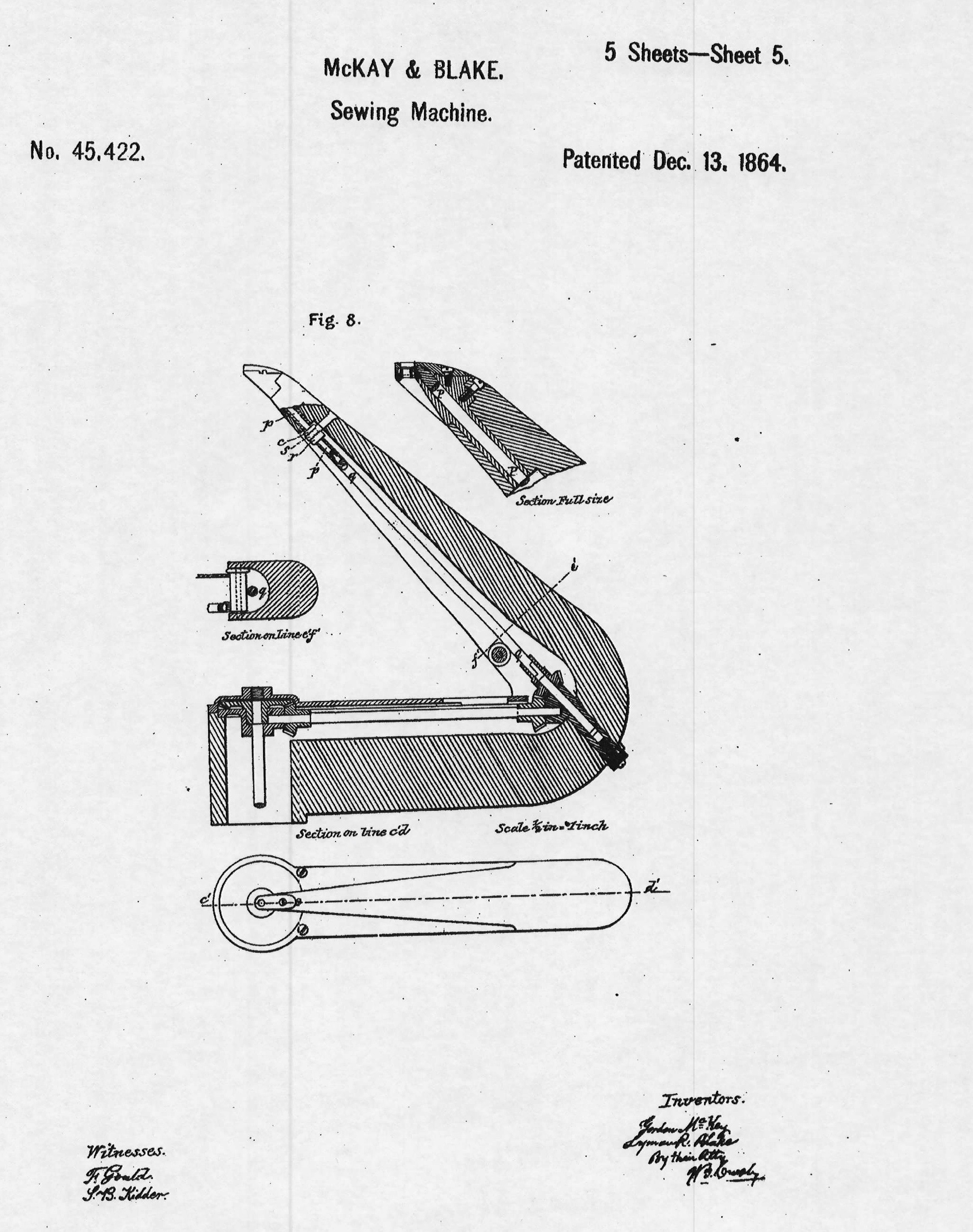

Blake took his knowledge of sewing machines and invented a thread carrying arm to fit inside the shoe that would stitch through the insole, upper, and finally the outsole itself. The arm created by Blake was hollow and rounded at the tip so as to allow the toe of the shoe to be stitched. The arm contained a mechanism for chain stitching and waxing the thread. A patent was issued to Lyman Blake in 1858.

Realizing that further development, eventual production and marketing were beyond his means, he sold his rights to Colonel Gordon McKay for $8000 in cash and $62,000 from profits in the company.

Blake went to Staunton, VA, where he established a retail shoe store. The war started and Blake took the last northbound train that was to run from Virginia for four years, leaving his store and $50,000 when he returned to Abington.

Nearly broke, Blake rejoined McKay and began the job of improving his machine and introducing the stitcher to the British Isles. While the machine bore the name of McKay in this country, it became known as the Blake machine in Great Britain.

With the Civil War in full swing, many shoemakers had joined the the army and shoe orders from from the army were nearly impossible to fill with the limited number of shoemakers available. McKay and Blake were able to install the machine in several New England factories. By 1862, thousands of pairs of shoes were sewn on the McKay stitchers. Shoemakers at the front, who had deserted their benches before the McKay machine appeared, used to study the shoes, and wondered how in the world any sort of machine could be made to sew shoes, particularly with the thickness of leather involved.

The outlook for the machine was bright but, still finding it difficult in selling the machine outright, McKay decided to lease them. The shoe manufacturers leased the machines and paid a per pair royalty to McKay. McKay’s idea of leasing caught on and is still in use today.

Colonel Gordon McKay

The McKay machine revolutionized the shoe manufacturing industry. It drew shoemakers from the little ten-footer shops, in which shoes had been handmade for decades, into the machine based factories. The quality of shoes improved dramatically while the cost to consumers was reduced substantially.

When Lyman Blake, as inventor of the McKay machine applied for a patent extension in 1876, he testified that from July of 1862 to July of 1876, 177,665,135 pairs of shoes had been sewn on the McKay machines, at an average savings of 18 cents per pair and a total savings of almost $14 million dollars.

Shoe manufacturers also testified that the McKay machines had enabled them to develop better manufacturing methods and to improve their product. Shoemakers testified that the machine had enabled them to decrease their hours and increase their wages, which benefited their health. When shoemakers worked by hand, they bent over their lasts much of the time, cramping their lungs. Consumption, as tuberculosis was then called, was a common disease among shoemakers. But, the prevention of it came, not from the science of medicine, but from the art of invention. The McKay machine, which Blake invented, enabled shoemakers to stand while working, and to breathe normally. As a consequence, cases of tuberculosis among shoemakers greatly diminished.

Colonel McKay and the Blake machine became an important factor in the formation of the United Shoe Machinery Company in February, 1899.