During the latter half of the 1800’s the shoe industry started on the path of mechanization, with upper sewing, sole attaching by stitching, pegging or metallic fastening and heeling all brought to at least a crude degree of development, further along this path. There remained, however, the immensely important problem of mechanizing lasting, the process which gives to shoes the major part of their visible shape. This was, perhaps, the most difficult problem of all because of the infinite variation of complex shapes and materials involved. Earliest efforts at mechanical lasting appear in English patents of 1844, followed by American patents in 1859 and 1860. In 1864 the American Lasting Machine Company was organized to market the invention of Williams Wells of Danvers, Massachusetts who had previously invented a pegging machine. In 1872 Colonel Gordon McKay, James W. Brooks and Charles W. Glidden formed the McKay Lasting Machine Association and bought the American company’s patents. They spent $120,000, an immense sum in those days, trying to evolve a good lasting machine from the patents and their own ideas.

In 1876 George Copeland patented and exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia the first practical lasting machine, a bed type. Working with F. Ballon, Erastus Woodward and Matthias Brock further patents followed into 1881.

Meanwhile the McKay group in a further effort to evolve a practical laster had absorbed a machine invented by Henry G. Thompson of Hartford, CT, on which $100,000 had been spent since 1873, and formed the McKay and Thompson Lasting Machine Association. Litigation over patents between the McKay and Copeland groups began promptly, lasted four years, cost more than $300,000 and neither group was making money. McKay won and was still seeking the best possible machine when he combined with Copeland to form McKay and Copeland Lasting Machine Association in 1881 resulting in a bed lasting machine, which was practical, but limited for use on heavy work. The royalty was set at 1/2 cent per pair for shoes and 3/4 of a cent for pegged boots.

About this time, Jan Earnst Matzeliger, a man worthy to be remembered along with Howe and Blake, was working at sewing shoes on a McKay stitcher at the Harney Brothers Shoe Factory in Lynn, Massachusetts. Matzeliger could only speak broken English and although there were many inventors and expert machinists with ample financial backing trying to produce a really good lasting machine at the time, it was Matzeliger working alone who made the breakthrough.

Jan Earnst Matzeliger

The whole Matzeliger story is interesting, not only by itself, but because it was this great invention as principle of the Hand Method Lasting Machine has never changed during the course of it’s production life.

Jan Matziliger was the son of a well educated Hollander who was sent out to Dutch Guiana in South America to oversee important government works. There he married a native Indian women and their son, Jan Earnst, was born in Paramaribo in 1852. The boy at the age of ten began training in a government machine shop under his father’s supervision as a machinist. He showed a remarkable ability to repair complex machinery and often did so when accompanying his father to a factory. His apprenticeship finished at age 19 when he decided to look for opportunities and explore other parts of the world. He worked aboard an East Indian merchant ship for a couple of years visiting several countries. Landing in Pennsylvania he decided to stay in the United States for awhile, eventually finding his way to one of the shoemaking centers, Lynn, Massachusetts at the age of 25.

Though earning his living stitching shoes on a McKay Stitching machine, Matzeliger was more interested in machinery than in shoes. He thought of making a turn shoe sewing machine, but he heard the hand lasters in the shop boast that whatever else might be done by machine, nothing could ever be invented to replace the hand laster. This was stimulus enough for Matzeliger. The lonely bachelor, already in delicate health, rented a room over the West End Mission and spent his evenings mocking up his ideas out of cigar boxwood, nails and other odds and ends on a model of a lasting machine which was to duplicate the actual operations of the hand laster by means of pincers and tacking mechanisms which progressively tensioned the shoe upper over the last onto the insole and tacked it there. This was in 1880. The crude model and its maker were much ridiculed, but there was one offer of $50 for the idea, and Matziliger was tempted.

Luckily he declined and set about making a second model out of some castings and old machine parts which he bought out of his earnings; patiently working alone forging, filing and fitting the various parts. This was a real machine and looked better. He was even offered $1500 for the device which pleated the upper around the toe. On the verge of accepting this offer, he concluded that if it was worth that much to someone else, it should be worth more to him.

A patent was issued to him in 1883, but only after the Patent Office had sent a man to Lynn to study, and try to understand the incredibly intricate motions in the machine and their useful purpose. A third and still better machine was patented in 1884.

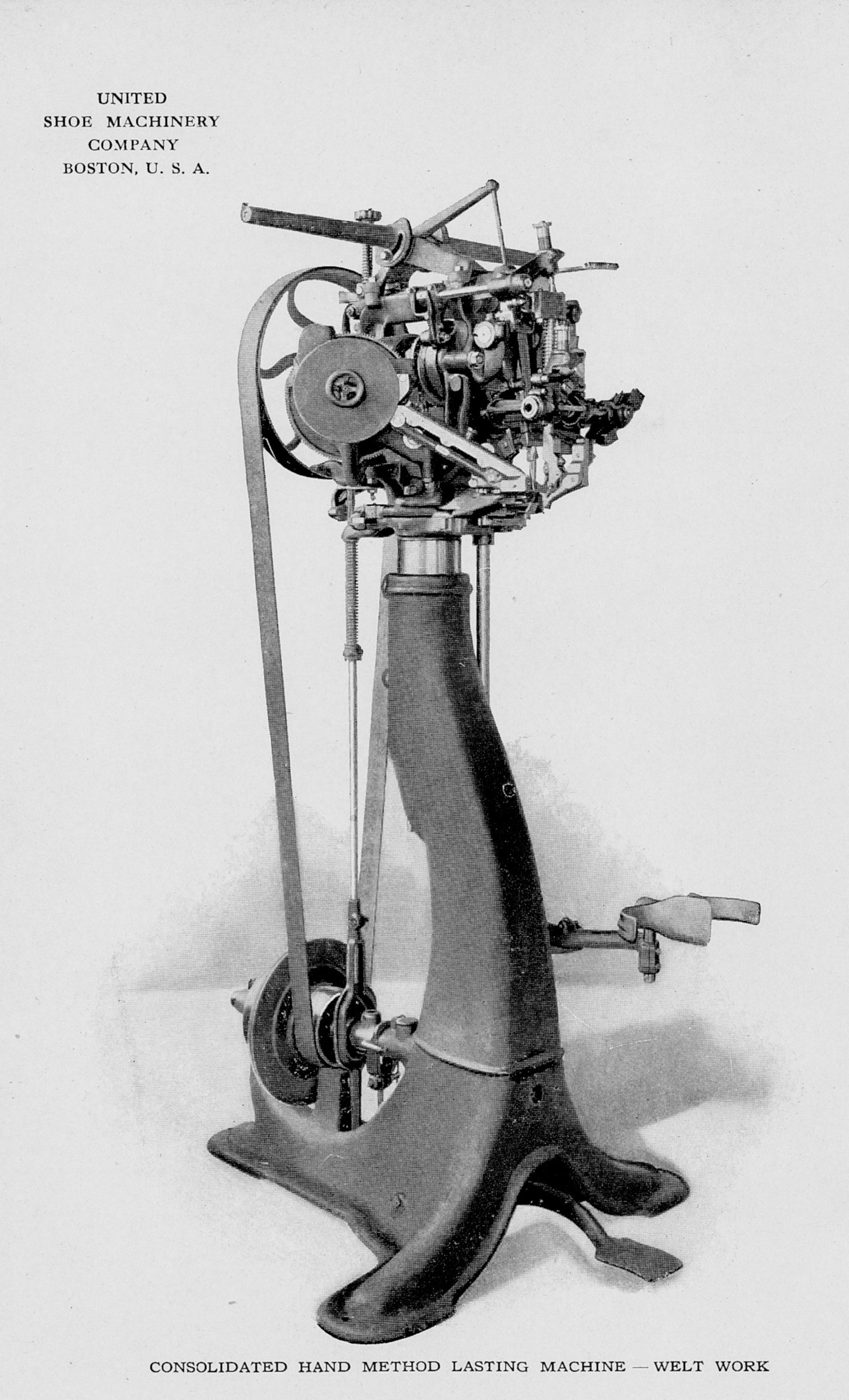

As a successful lasting machine, local manufacturers were interested and formed the Union Lasting Machine Company, in1884 which became the Hand Method Power Lasting Machine Company in 1885 and the Consolidated Hand Method Lasting Machine Company in 1887. Sidney W. Winslow bought stock and hired experts to assist Matzeliger. It was the Consolidated Hand Method Lasting Machine Company that commanded the highest per share price of the constituent companies forming the United Shoe Machine Company in 1899.

Sidney W. Winslow, one of the founders of the United Shoe Machine Company

Matzeliger went on working as he was able, on improvements until his death in 1889 from tuberculosis at the age of 39. His good works lived long after him. Not only have thousands of his excellent lasting machines operated for many decades throughout the world, but in 1904 the North Congregational Church of Lynn, ceremonially burned its morgage, discharged by the sale of United Shoe stock acquired in exchange for the Consolidated Hand Method stock bequeathed to them by Matzeliger.

Photo by Charles Williams

Good as it was, the Hand Method Machine did not get on the market without trouble. The hand lasters in Lynn resented it, fearing for their livelihood. In those days such resentment frequently expressed itself in direct action, sometimes with violence. The lasters had a formidable organization and they considered themselves the aristocracy of the shoe factory. There was a series of pitched battles; some manufacturers were driven out of Lynn and some out of business. In the end the hand lasters learned to run the machines (which really made their work easier and more productive) and peace was restored.

Photo by Charles Williams

Photo by Charles Williams

Model HM for side lasting McKay shoes.

Model HM setup all around lasting of McKay shoes.

Model HM-M

Model HM-L

Catalog page from a USMC 1914 Catalog